About Refugees, By Refugees

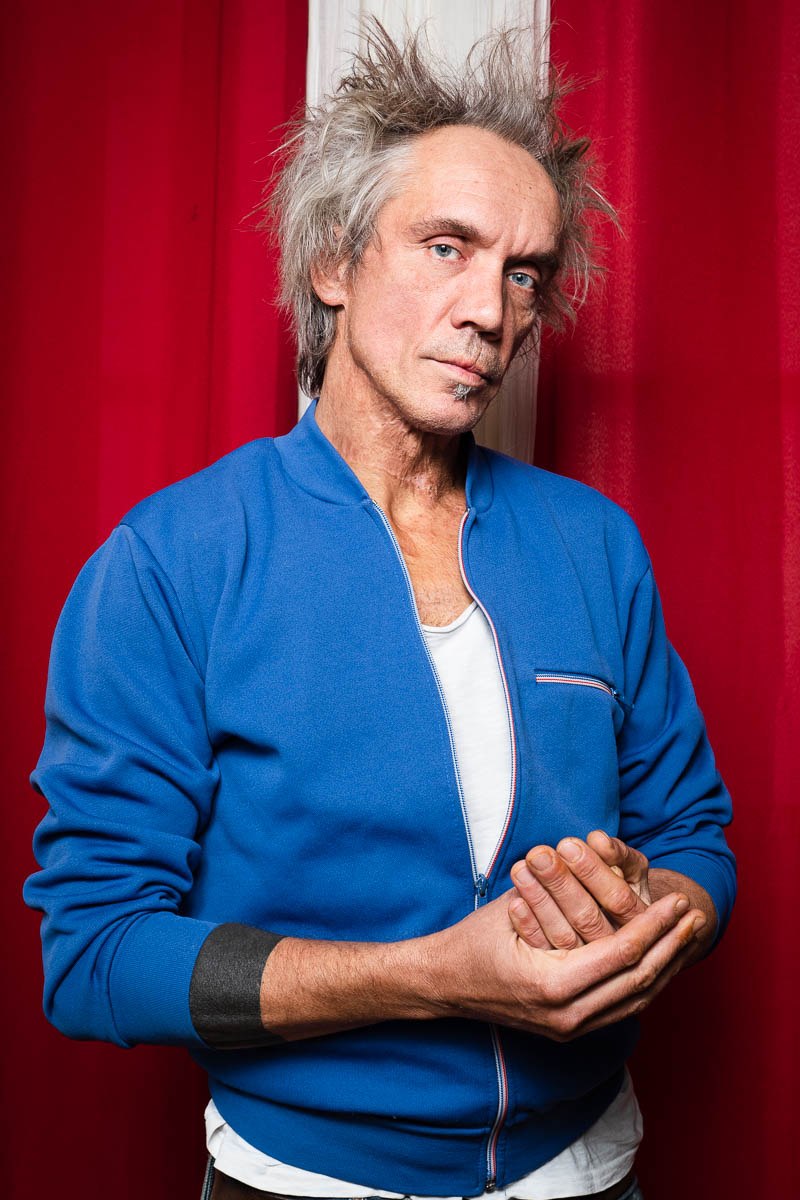

Nedžad Ajkić

Pictures taken in:

From:

Nationality:

Photo and interview by:

Greece

France

French, Bosnian

Mirza Durakovic

“I would say that my dream would be… to have a vehicle fitted out and to go around the world and draw people,” says Nedzad Ajkic (46), a French and Bosnian artist living in Paris. Born in France, at age 10 he moved to Yugoslavia with his family. When he was 17 they returned to France, fleeing the Yugoslav Wars. “We sensed the tension that was coming. Political divisions, the first conflicts of people between themselves.” Leaving was “very, very complicated. I remember, after 50 km, a bunch of guys stopped the bus we were leaving in to get to Zagreb and pulled us all out… I remember they traumatized me a little.” Nedzad feels guilty that he left. “I suddenly left everything and then, from afar, I heard how it all ended, they are all at the front, there is the other who died, the other he’s missing two arms…” He has faced other challenges, too, but, “whatever the period of my life, drawing has always accompanied me to overcome these difficulties.”

Trigger Warning:

full interview

Hello, hello Nedžad!

Hello, Mirza.

Can you introduce yourself, just for the project? What’s your name?

I’ll try to do the best, at the shortest. My name is “Nedzad Aïe-kitche.” My name is also “Nedzad Age-kique”. It depends on who I’m addressing. I was born in 1974 in Paris. I stayed in Paris until I was 10 years old and from 10 to 17, I went to Yugoslavia with my parents. The war began. I returned to France to continue my studies in France. First to finish college, and then graphic art and visual communication studies. So today, I live and work in Montreuil as a graphic artist, illustrator. I have several caps, in the visual communication sector anyway.

And you live in Montreuil. In an apartment, a house?

I’m in an apartment that I managed to acquire and build, rebuild, and in which I live with my darling, and my cat.

And your cat. And so, are you happy with your living conditions, etc., or would you like to have a house or what…?

Ah, I aspire to a lot more space. I aspire to a studio, nature and ideally, continuing to carry out my work but often it’s not… I guess it’s not very compatible to work in my sector and at the same time live isolated. Ideally, I aspire to isolation in nature.

Okay. So how do you feel in Paris, Montreuil and Paris?

Very good, very good. I have always lived in Paris and from the day I moved to Montreuil, I decided to never return to live in Paris again. We have much more space here, more than 50% of the population works in the arts sector. I have an interesting community living in Paris – in Montreuil, sorry – and who, there’s a group of friends, there are people who we see, who we don’t see. I really like to be in Montreuil, anyway, as much as possible. This is a city that I chose and in which I feel pretty good.

And to get back to what you said, so you said you were born in France, can you tell me a little about your first years and how, did you feel French, did you feel Yugoslav? How’d it go?

You mean the first years since I was born?

Until the moment you returned to Yugoslavia.

Yes. Yes, I never felt foreign. I always felt French, much more than Yugoslav. But I knew I was Yugoslav, because my parents were Yugoslav so at home, we spoke Yugoslav. And I also have a name – and a first name – which is very marked. So, little by little, I realized that I was not of French origin, because I really had a first name, I mean, I really have a name that is identifiable. But I always felt integrated, totally, the same as my fellow people at school. And I was in the 1st arrondissement, that’s where I grew up, near Étienne Marcel, in a multicultural school, with many different origins, so there were no more French than Maghreb. There were even four Yugoslav people in my class.

And do you remember how you felt when you came back to Yugoslavia?

Erm, yes.

How old were you? About 10, yeah, 10 years old. I arrived there too, with, certainly a kind of pretentiousness. I arrived there saying, “I am French, you’re not French”. So very quickly, I was put in my place. I learned things that I had never learned in France before, including the relationship with nature, animals, fishing, late games in the evening on the street. I felt a great pleasure in this new way of living and in addition, schooling is not at all the same. There, we go to school only in the morning or in the afternoon. There’s no school holidays as long as in France. So they were new habits to get into. But very quickly, I got them, I integrated them with no problem.

What year was this?

So, I left France in ’83.

Okay. And do you remember the events that led to the war?

Yes, very well. I was right in the middle of it and we felt, we sensed the tension that was coming. Political divisions, the first conflicts of people between themselves; political divisions often marked by religious affiliation. And then, little by little, the first conflicts of ’91 and so late ’91, a little bit in-extremis, I managed to leave Yugoslavia to return to France. But yes, yes, I felt them when they came. ’89-’90 already, it was quite tense.

And do you remember how you felt at that time? Were you scared? Were you confused? What were the feelings that predominated in you?

Well at that time, precisely, I was 15-16 years old. What I was most concerned about was… I didn’t have these feelings yet, for me, it was obvious that there would be no war. What worried me was: will I go out tonight, will I be playing basketball, will I go fishing. So yeah, I was more concerned with questions of my age. But we didn’t feel the possibility yet, I think very few people, not many people anyway, were surprised by the sudden way the war came, the first attacks and the first conflicts.

Do you remember where you were when it started?

Yes, so it was my first year of electrical engineering. It’s a school I chose to do because basically there weren’t too many choices when you’re in Bihać – the city where I grew up – when you’re a boy, you do electrical engineering and when you’re a girl, you go to textile school. Basically, that was how things went so a lot of boys were in that school, so I was in that school, too. And so that was in ’91, ’90-’91. I was already beginning to feel conflicts, if only with my teachers who were not of the same faith as me, who sent me back to my origins. I did not understand why, having done the same job as Darko or Mladen, Nedžad had a score that was lower. It happened to me several times. My parents were alerted to this kind of thing too, they went to see the teachers, so there were conflicts already beginning between people and that’s where I felt that there were separations that were operating. And then, very, very soon afterwards, the events with Croatia, so ’91-’92, and it was at the end of ’91 that we decided to leave before it seriously broke. I still had the opportunity to return, I was 17 years old, I could still apply for my nationality in France, and so I came back and made all the necessary steps to obtain nationality.

Would you describe this departure as a flight because you still wanted to stay in Bosnia?

Yes, a little bit, because, well I really wanted to go to an art school and for me it wasn’t possible in Bosnia. So that year, ’90-’91 I was not a good student at all. I’ve never been a bad student, but that particular year I wasn’t going to school, I was running away from school, spending a lot of time on basketball courts. I drew a lot too, so I was isolated often. In any case I went very, very little to school and I was criticized a lot about that. So for me, it was in a way an opportunity to leave a school that didn’t suit me. But at the same time, it was very, very painful because I left all my friends, all my family there. We left with my parents and sister. And then, to leave, it was very, very complicated too.

Do you remember the way?

Yes. I remember, after 50 km, a bunch of guys stopped the bus we were leaving in to get to Zagreb and pulled us all out of the bus. And that they looked me right in the eyes in a nasty enough way to ask me, “What am I doing, where am I going?” I don’t know who they were exactly, but I think they were sort of wild checkpoints, improvised by people who wanted to see if there was anything to take on this bus or not. I don’t know who they were exactly but they were not beautiful soldiers to see, whatever their vocation. I remember they traumatized me a little, I felt a control like that, difficult. And then the most complicated thing for me was to be in France and find that the war started, and then start counting the dead.

Do you remember how you felt returning to France once here?

Once back here, I tried to incorporate the codes of a schooling of a secondary school student who arrives and settles in France. I was 16 and a half, 17 years old and I was put in ninth grade, so I was 17 years old when all my classmates were 14 or 15, but I didn’t have a French level good enough to, for a… It was also not too bad to be in a non-francophone class, so they said we will put him in ninth grade. Anyway, so I was ninth grade with children who were 14, 15 years old and… Well, I have an anecdote, I noticed that there were those who played basketball, they had Nike – there are codes like this that did not exist in Yugoslavia – so I didn’t have Nike, I didn’t want to have any, but I had a sweatsuit like the one I wear today where I embroidered and drew the sign of Nike. I thought like that I’d be buddy with those who play basketball at school. So it turned against me very violently… Not violently, but they jerked me around. So I spent a rather difficult year in secondary school when I returned to France, because older than the others, but yet considered like someone who has no experience, at least not theirs. And then, very quickly afterwards, I went for an art school, where there it began to be more comfortable.

Would you say art helped you overcome these difficulties?

Ah, whatever the period of my life, drawing has always accompanied me to overcome these difficulties.

And your relationship to the country of origin, once you were here, those first years, how did you see Bosnia? What happened when you were thinking about Bosnia? Did your parents tell you a lot about it? Were you interested in what was going on there?

So I had a lot of friends in France. When I came back, so 17-18 years old, I still turned a lot to a Yugoslav community and went out to places where there was rock music that I knew and recognized, in which I had immersed myself before coming. And in those circles, I also met friends. I never cared too much if they were Serbs, Bosnians, or Muslims, or Orthodox or Catholics. These are things that have never – even today – been decisive for the choice of the people I’m with. But it was then, yes, that I realized that some, on the other hand, had bad opinions about me, because I wasn’t from their community. So little by little, I also stopped frequenting the Yugoslav group, because still loaded with preconceptions and prejudice, just because you bear a name that sounds a bit Muslim.

When did you stop…?

Oh, I must’ve been 20 years old, 19-20. It was especially from that moment that I turned to an artistic environment where, surprisingly, I haven’t met a lot of people from Yugoslavia, but well, I was mostly with, let’s say with French people who grew up in France, and who were moving towards an artistic profession. I also worked a lot in my profession with Yugoslavs, mainly musician artists, because there are still many musicians artists in Yugoslavia and who are settled in France as well.

Did you look for this connection with the community? Was that something voluntary on your part? Or did it come by chance, like that?

More by chance, but undeniably also that I had to look for it somehow. But it was never a step, it was never a step. Neither to them nor to the French, it was, uh a combination of factors, and meetings.

And when we wrote, you told me that you consider yourself a half-refugee, ‘polu-izbeglica’. Yes.

Can you explain a bit, why is that?

Well, what I like to say sometimes is that I’m a second generation Bosnian immigrant. My father is an immigrant, he arrived in about ’70 in France. I was born in France, but then, when I went to Yugoslavia, my little nickname there was “Francuz” – “the French boy” – and returning to France, I was regularly made to understand that I was a foreigner. So there is this phenomenon of “stranger here, stranger there”, which I actually like because the idea of having a homeland, I admit, is not at all anything that animates me. I’m not attached to one country more than to another. Yes, I am more attached to France and Bosnia than to Belgium, of course, but I do not feel more French than Bosnian. Even though I say that, but still, I still feel a little more French, but I don’t really know. So half-immigrant, why? Because there, it’s this situation of being sometimes, well, I spend quite a lot of time with my parents or at least once a year I go to Bosnia, there is like a switch that’s happening in me… When I speak Yugoslav or Bosnian, I have a different voice than when I speak French. Another intonation, another, not another personality, but almost.

Okay, and you said half-immigrant, but half-refugee is not exactly the same thing, so…?

Not at all, I don’t know, I don’t think that…

Would your parents have stayed in Bosnia, do you think, if there hadn’t been a war?

Yes.

And would you have stayed too?

I would have done everything I could to ask them to let me, to make sure that I joined a school that interests me because otherwise, I would not continue in an area that was electrical engineering, which was absolutely not interesting for me at all. So maybe I would have managed to convince them, at the age of 18, to return to France to try to join a school. There would have been no war, it would be either France, or it would be a big city in Yugoslavia, like Zagreb or Sarajevo, I don’t know, where there are art schools that are notable, almost. But, uh, for me, France was also the idea of the capital of art where I was going to find my happiness in schooling. So yes, no I really wanted from the age of 16 to 17 to return to France, as far as schooling was concerned.

Okay. Are there still things from that time, the war, etc., that follow you and that you still think about?

Yes, yes, a lot, every day. Every day. Especially one day, I earned a lot of money in one day, while I did nothing and it broke me down because so much money is the equivalent of four salaries of any of my cousins who are… I really say four wages, I mean four months’ salary, sorry. What happened was that I was asked to come to draw portraits of people at a seminar, so I came. No one came to get drawn. I was still paid by the day, so for three days I was given 1,000 euros a day. So, after three days, I got 3,000 euros and nobody came to get drawn. They all wanted to eat appetizers, chat with each other. This animation here, this attraction there, did not interest them, and even worse, at the end of the second day I was told, “Listen, nobody is interested in this, go home, it’s okay. You’ll be paid three days anyway”. So I was delighted, but when I got home I broke into tears in the subway because I thought about the situation of some of my cousins, friends who, for ten euros, will work all day to clean a bar, to do the service, to do the checkout, to do the account, to close the bar, to throw out the last drunk and will earn 7-8 euros.

And in relation to the events and what happened during the war, and all that, are there things that come back too?

There are small traumas. I wouldn’t call them big traumas, but small, it can be translated into the form of a dream or a… (Thinking). I am easily satisfied with everything at the end of the day because I think it could have been much worse if I had stayed there. At the same time, it’s a strength, but nothing very, too traumatic or things like that.

Okay. And where do you find strength – I imagine in your art – but where do you find strength, in general, to overcome these kinds of difficulties when you think about it or when you think about the country?

It’s going to be a lot in some very precise pieces of music that are from there. It can be from time to time images and photographs, or thoughts. But I find, I mean I don’t think I need to look for strength somewhere, it’s also a memory of my childhood and I have spent much, much more time in France than in former Yugoslavia. But the period I spent in the former Yugoslavia is very important. It remains, well between 10 and 17 years, we learn a lot of things from life.

And so do you remember at that time, in that period, precisely where we learn a lot, what was your dream actually at that time? And for the project, they actually ask that it be said, if you can answer, “My dream, before coming to France, my dream was to…”

Before coming to France, returning to France, my dream was really to have a job which is at the heart of one, to have a passion that is my job. Yes, it was really my desire to work in the field of drawing and visual communication. Or in any case to evolve in this environment and not in another. It could be…

And what about today? If you can also repeat the same sentence again, “Today, my dream is to…” Do you have a dream today?

Given the current international situation, it is very, very difficult to look to the future. But yes, I can say that my dream would be… I don’t have great material needs, but to have strictly the minimum, I want to say necessary, which allows me to be well and to be elsewhere than in a city. To have a large space to be able to produce, to work and possibly have a more personal artistic production, less oriented towards industrial control, and why not aim at the art and exhibition market. This is a vocation that I have never developed, I have always responded to orders. I’m not an artist, I mean I’m not someone who’s in his studio, producing for an upcoming exhibition.

So if you can just say, like, “My dream would be to…” What, to become an artist who produces and exhibits his works, for example? Would be it, or…?

We can say that. I would say that my dream would be to stop responding to orders related to the industrial sector and to make graphic arts and illustrated visuals, more personal and more unique works, indeed, rather than things that are drawn at 10,000 or 50,000 copies. So yeah, to be… More independence. Independence, it’s true that it’s something that is very important to me. So I’ve always been independent, I have been very little paid as a salaried employee in my life. Very quickly, when I got out of school, I aimed at independence and freelance.

Well, thank you.

Isabelle, Nedžad’s girlfriend: You could also say: go in a truck, draw around villages and draw people?

That, yeah, it’s one of the dreams, this one. Thank you, Isabelle. Indeed, this one is… If I had money, enough not to worry, “Where am I going to find money? How am I going to eat at the end of the month?”, the ideal would be to have a vehicle fitted out and to go around the world and draw people and their living environment, that is, portraits or artists in their workshops, with their tools, to draw, distribute, give my drawings, sell them…

Draw the world?

Draw the world. Or redraw it. And yes people, I really like…

People especially.

I really like the question of, not really portrait, actually yes, it’s the portrait or the caricature, it doesn’t matter but… The people.

Isabelle, Nedžad’s girlfriend And the interaction too.

And the interaction too, the interaction it fosters, of course. Because, ideally, if I could, yes, go, I don’t know, to Africa, in exchange for ten drawings, that I get offered two, three nights in a box with tiep chicken or mafé, yeah, move around like that. So that is a material exchange, but other than that, meeting with people and giving them the best of myself while I don’t have it… I mean It’s not something I bought somewhere, it’s something I know how to do and I know that a child maybe… I’ve already seen this in a child, or a man or a woman, whatever, but people can be very, very happy with a drawing and it really doesn’t require much of me, and I can do it. So having this exchange with the world, I would like that a lot.

Okay, thank you very much Nedžad. And one last general question that I always ask is: is there something you would like to add on the subject of refugees, something that you would have, I don’t know, anything you would like to to say, anything in particular you would have experienced or realized maybe?

Refugees, yes, foreigners, immigrants, these are all notions that have been invented by minds – not necessarily nationalist minds – but the statistics are upfront: there are more and more foreigners in the world. This is undeniable. You can’t say that… That’s how it is, population movements have always existed, sometimes we called them refugees, in other times, we called them travellers. So yeah it’s erm, I don’t know if I’m answering the question?

No, no, it’s just, do you also think like that?

Yeah, yeah. I remember a sentence I had read which really said, “Statistics are upfront. There are more and more foreigners in the world”. I like that phrase because we’re all a stranger to someone, we’re all migrants, we don’t know what’s waiting for us in the future. I also remember a picture where… It is a boat that’s leaving the port of Marseille, it’s in ’45 and it’s French people fleeing the Nazi regime, en masse, for African lands and it is a boat that is filled, filled, filled with people. So yeah, France also could have been a country that wanted… It all depends on the history and its unfolding. I don’t know how to say it.

A land of exile, you mean.

Yes, a land of exile and of exiles and exilers… Yeah. Anyway, today I have nothing against people who come from elsewhere, on the contrary. I think it has always been enriching for me to meet with different viewpoints and visions and perspectives and languages.

Thank you Nedžad!

Isabelle, Nedžad’s girlfriend Can I add something here? I don’t think you talked about important things like the fact that you threw the TV when you were 19 years old.

There’s a lot of things I haven’t quoted on, that’s true… I didn’t think of that, that’s true.

Isabelle, Nedžad’s girlfriend That’s why I’m telling you. It’s your look at what was going on there when you were there, and how you might have suffered from it.

Yes, in relation to this question.

Isabelle, Nedžad’s girlfriend It’s part of this subject, I think. And it’s important.

Yeah, that’s very fair. I didn’t mention my accident in ’94. I didn’t talk about…

Isabelle, Nedžad’s girlfriend That, and the TV.

Yeah, yeah, I want to know more about that. Thank you, Isabelle.

What happened, indeed, is that in ’93 – here we are in 2020 – since 93, I don’t watch TV anymore at all. I have never had a TV, I watch very little news, I find things out on different channels. But in ’93, between what they said – it was Patrick Poivre d’Arvor at the time and Marie Claire Chazal – it was totally wrong. It was wrong. Clearly, it was wrong. I had news on the phone, it was wrong what they said about… We will not give names, but still, historically speaking, it was at the time of General Morillon, it was at the time of Mitterrand, at the time of what they were doing, what was happening in Srebrenica. We were in ’94 more precisely – if I’m not mistaken – in ’93-’94. And it made me hallucinate about the reality of this world that informs and that… It was the largest national channel that said things to the whole of France which were false, false, false, and oriented towards the peacekeepers who were there for good reasons, which is necessarily fair too. But the way they lied on television, it made me very, very frightened. Which led to, that day, I calmly took the TV, took it out on the street, I unplugged it. I took it out on the street, put it outside. My father came home from work in the evening, he said, “Where is the TV?,” I told him that he shouldn’t watch this. So I got a little yelled at because I threw the TV out. So he went to pick it up, but someone had already taken it. But I, since about ’93, I’ve had a great, great distrust because it’s the winners who write history and that they even write it while it’s unfolding. So I don’t believe too much in the news if it’s not live, at the very source. So there was that, and then the second thing that’s astonishing is that I had a big accident in ’94 and stayed in the hospital for a year and a half, right at the time when many of my cousins, fellows, died, too. I almost went, too, while I was in France. Maybe it’s important, but…

Did you think about it when you were in the hospital?

Yes, yes, a lot. And a lot of cousins from there were worried about me because they knew I was in a critical situation. I was in a coma for 4 months. And so yeah, they worried about me but I wasn’t at all in a situation, I mean in a country, in a war situation, but yet, I was in the same conditions of repair and survival.

Isabelle, Nedžad’s girlfriend On the question of guilt compared to others. There is a bit of that, isn’t there? To ask yourself this question of whether this accident happened to you because you were feeling guilty about having your class friends who were dying there, while you were in Paris, all chilled out.

It’s really an accident, it’s not a suicide attempt, you know.

Isabelle, Nedžad’s girlfriend No! But, I mean I don’t know… But when you told me about it or what, there was still this question, that you felt a kind of guilt for being there, while they were there.

At that time, as soon as the war started, yes, I had no desire to go to war or anything, but I was not good because I knew they were locked in a… I just want to remind here that I left at about 16 and a half. I really had lots of girlfriends, I had lots of male friends, I had clubs where I was registered for chess, and fishing and basketball especially, and in drawing. I suddenly left everything and then, from afar, I heard how it all ended, they are all at the front, there is the other who died, the other he’s missing two arms… So yeah, so I felt a little guilty of not also being in… Of having left. I certainly accused myself at one point of having fled. But they also reassured me by saying, “Don’t worry, everyone who had the opportunity to leave, they left. Those who stayed were those who had no opportunity.” I had the opportunity to leave because I had this dual nationality which meant that I was born in France too. So they let me leave the territory. But there are many who tried to get out who did not succeed.

And your parents applied for asylum here, or did they have the nationality?

Erm no, they asked for nationality because they’ve been here for a very long time, they had children here, they built things here, so.

So they applied for it at the same time as you did when you came back?

No, much later.

Later, okay.

Much later. They’ve been French for about 20, 15 years.

So they had asylum seeker status when they arrived?

I couldn’t tell you.

Yeah, probably since you don’t have a visa. Anyway, it’s a technical question. It doesn’t matter. Okay, so that’s super interesting, this guilt thing…

Yes, that’s true, it’s… Maybe I kinda suppress it, but yes, very often, very often, at least once a day at that time, there was something that happened that we heard about on the phone, because we still had telephone communication until ’94, ’95. Afterwards, it was much more difficult. But we had very regular news of what really happened, of who was gone, how he went, and they’re very, very close people.

Do you remember how you handled this feeling of guilt? Did it disappear little by little or was there a trigger moment, a moment when you thought to yourself,“No, I have to stop”?

No, I didn’t, I’ve never triggered… I mean, this feeling of guilt is not that strong. It is very present today, as much as it was at the time. I know that at one point, I left and left people I love to be butchered. But it was able to leave me when one day, a philosopher friend reassured me by telling me that all those who could leave left and it is the same Emir, the same friend sorry who is called Emir – who is very interesting as a profile too – who immigrated to France, he arrived from Tuzla, he arrived in ’98. He has a PhD in Bosnian Philosophy but here in France, his diploma is not recognized, he is a laborer and works here and there. I met him on the subway when I came back from those three days when I had earned 3,000 euros doing nothing. And I cross paths with him, I’m crying in the subway and he says, “What’s happening to you? I’m Emir, etc.” And then, Emir once again managed to reassure me by saying, “If you offer me 50,000 euros a day so that I can go draw someone, I will say no, because I can’t draw”. He made me understand that, yes, so I know how to draw, so I was there because I knew how to draw, not to draw. If I had drawn someone, it would have been good, but in any case, I would have been able to do it if someone had come saying, “Here, I want my portrait”, I would have been able to do it. That’s what counts, it’s the ability to do things. It’s important. I knew to be surrounded and reassured by a group of friends who are kind.

Okay. Well great, thank you.

Many 1000 Dreams interviews were not conducted in English. Their translation has not always been performed by professional translators. Despite great efforts to ensure accuracy, there may be errors.